Saint Sebastian (traditionally died January 20,[1] 287) was a Christian saint and martyr, who is said to have been killed while the Roman emperor Diocletian engaged in the persecution of Christians in the 3rd century. He is commonly depicted in art and literature tied to a post and shot with arrows.

Life

The details of Sebastian's martyrdom were first elaborated by Ambrose of Milan (died 397), in his sermon (number XX) on the 118th Psalm. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, states that Sebastian came from Milan and that he was already venerated there in the fourth century.

According to Sebastian's fifth-century Acta,[3] still attributed to Ambrose by the seventeenth-century hagiographer Jean Bolland, and the briefer account in Legenda Aurea which is followed here, he was a man of Gallia Narbonensis who was taught in Milan and appointed as a captain of the Praetorian Guard under Diocletian and Maximian, who were unaware that he was a Christian.

Sebastian was reportedly known for having encouraged in their faith two Christian prisoners due for martyrdom, Mark and Marcellian, who were bewailed and entreated by their family to forswear Christ and offer token sacrifice. His aura cured a woman of her muteness, and the miracle instantly converted seventy-eight people.

According to tradition, Mark and Marcellian were twin brothers and deacons. They were both married, and from a distinguished family. They both lived in Rome with their wives and children. The brothers refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods and were arrested. They were visited by their father and mother, Tranquillinus and Martia, in prison, who attempted to persuade them to renounce Christianity.

Sebastian ended up converting Tranquillinus and Martia, as well as Saint Tiburtius, the son of Chromatius, the local prefect. Nicostratus, another official, and his wife Zoe were also converted. According to the legend, Zoe had been been a mute for 6 years. However, she made known to Sebastian her desire to be converted to Christianity. As soon as she had, her speech returned to her. Nicostratus then brought the rest of the prisoners; these were 16 people who were also converted by Sebastian.[4]

Chromatius and Tiburtius became converts; Chromatius set all of his prisoners free, resigned his position, and retired to the country in Campania. Mark and Marcellian, after being concealed by a Christian named Castulus, were later martyred, as were Nicostratus, Zoe, and Tiburtius.

Martyrdom

Diocletian reproached Sebastian for his supposed betrayal, and "he commanded him to be led to the field and there to be bounden to a stake for to be shot at. And the archers shot at him till he was as full of arrows as an urchin is full of pricks,"[5] leaving him there for dead. Miraculously, the arrows did not kill him. The widow of St. Castulus, St. Irene of Rome, went to retrieve his body to bury it, and found he was still alive. She brought him back to her house and nursed him back to health. The other residents of the house doubted he was a Christian. One of those was a girl who was deaf and blind. Sebastian asked her "Do you wish to be with God?", and made the sign of the Cross on her head. "Yes," she replied, and immediately regained her sight. Sebastian then stood on a step and harangued Diocletian as he passed by; the emperor had him beaten to death and his body thrown in a privy. But in an apparition Sebastian told a Christian widow where they might find his body undefiled and bury it "at the catacombs by the apostles."

Of the miraculous effect of the example of Sebastian, Legenda Aurea reports

- "And Saint Gregory telleth in the first book of his Dialogues that a woman of Tuscany which was new wedded was prayed for to go with other women to the dedication of the church of Sebastian, and the night tofore she was so moved in her flesh that she might not abstain from her husband, and on the morn, she having greater shame of men than of God, went thither, and anon as she was entered into the oratory where the relics of Saint Sebastian were, the fiend took her and tormented her before all the people."

Sebastian was also said to be a defense against the plague. Legenda Aurea transmits the episode of a great plague that afflicted the Lombards in the time of King Gumburt, which was stopped by the erection of an altar to Saint Sebastian in the Church of Saint Peter in the Province of Pavia.

Location of Remains

The remains asserted to be those of St. Sebastian are currently housed in Rome in a basilica that was built by Pope Damasus I in 367 (Basilica Apostolorum), on the site of the provisional tomb of St. Peter and St. Paul. The church, today called San Sebastiano fuori le mura, was rebuilt in the 1610s, under the patronage of Scipio Borghe.

Depictions in art and literature

The earliest representation of St Sebastian is a mosaic in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo (Ravenna, Italy) dated between 527 and 565. The right lateral wall of the basilica contains large mosaics representing a procession of 26 Martyrs, led by Saint Martin and including Saint Sebastian. The Martyrs are represented in Byzantine style, lacking any individuality, and have all identical expressions.

Another early representation is in a mosaic in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli (Rome, Italy), which probably belongs to the year 682, shows a grown, bearded man in court dress but contains no trace of an arrow"[6]

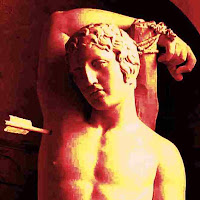

As protector of potential plague victims and soldiers, Sebastian naturally occupied a very important place in the popular medieval mind, and hence was among the most frequently depicted of all saints by Late Gothic and Renaissance artists. The opportunity to show a semi-nude male, often in a contorted pose, also made Sebastian a favourite subject. His shooting with arrows was the subject of the largest engraving by the Master of the Playing Cards in the 1430s, when there were few other current subjects with male nudes other than Christ. Sebastian appears in many other prints and paintings, although this was also due to his popularity with the faithful. Among many others, Sandro Botticelli, Andrea Mantegna, and Perugino all painted Saint Sebastians, and later El Greco, Gerrit van Honthorst and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. [7]

The saint is ordinarily depicted as a handsome youth pierced by arrows. There were predella scenes, when required, often of his arrest, confrontation with the Emperor, and final beheading. The illustration in the infobox is the Saint Sebastian of Il Sodoma, at the Pitti Palace, Florence.

A mainly seventeenth-century subject was St Sebastian tended by St Irene, painted by Georges de La Tour, Jusepe de Ribera, Hendrick ter Brugghen and others. This may have been a deliberate attempt by the Church to get away from the single nude subject.

There exist several cycles depicting the life of Saint Sebastian. Among them, the frescos in the "Basilica di San Sebastiano" of Acireale (Italy) with paintings by Pietro Paolo Vasta.

In his novella Death in Venice, Thomas Mann hails the "Sebastian-Figure" as the supreme emblem of Apollonian beauty, that is, the artistry of differentiated forms, beauty as measured by discipline, proportion, and luminous distinctions. This allusion to Saint Sebastian's suffering, associated with the writerly professionalism of the novella's protagonist, Gustav Aschenbach, provides a model for the "heroism born of weakness", which characterizes poise amidst agonizing torment and plain acceptance of one's fate as, beyond mere patience and passivity, a stylized achievement and artistic triumph.

Egon Schiele, an Austrian Expressionist artist, painted a self-portrait as Saint Sebastian in 1915.

During Salvador Dalí's "Lorca (Frederico Garcia Lorca) Period", he painted Sebastian several times, most notably in his "Neo-Cubist Academy". For reasons unknown, the left vein of Sebastian is always exposed.

George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four makes a reference to Saint Sebastian when the protagonist, Winston, fantasises about tying another character, Julia, to a stake naked and shooting her "full of arrows like Saint Sebastian".

In the novel Fabiola by Nicholas Wiseman, Sebastian is portrayed both in his glory days as a well-loved centurion and commander, and also in his days of martyrdom. He appears as a friend of the main character, the Roman lady Fabiola, and her father.

Patronage

As a protector from the plague, Sebastian is sometimes counted as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. The connection of the martyr shot with arrows with the plague is not an intuitive one. In Greco-Roman myth, Apollo, the archer-god is the deliverer of pestilence; the figure of Sebastian Christianizes this familiar literary trope. The chronicler Paul the Deacon relates that Rome was freed from a raging pestilence in 680, by the patronage of this saint.

Sebastian, like Saint George, was one of a class of military martyrs and soldier saints of the Early Christian Church, whose cults originated in the 4th century and culminated at the end of the Middle Ages, in the 14th and 15th centuries, both in the East and the West. Details of their martyrologies may provoke some skepticism among modern readers, but certain consistent patterns emerge that are revealing of Christian attitudes. Such a saint was an athleta Christi, an "athlete of Christ", and a "Guardian of the heavens"

Saint Sebastian is the protector saint of the cities of Qormi (Malta), while is the patron saint of Caserta (Italy). Saint Sebastian is also the patron saint of the cities of Palma de Mallorca and San Sebastián (Spain), where on January 20--a public holiday--there are street festivities and celebrations.

He is also the patron of San Sebastian College - Recoletos, Manila, one of the Philippines' foremost institution for higher learning. Beside it, is the sanctuary of the Parish of San Sebastian, which is also the Philippines' National Shrine of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel.

In the Greek Orthodox Church, the feast day of Sebastian the Martyr is December 18. In the Roman Catholic Church, his feast day, set on January 20, is not mandatory.

Officially, Saint Sebastian is the patron saint of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Informally, in the tradition of the Afro-Brazilian religious syncretism Umbanda, Saint Sebastian is often associated with Ogum, especially in the state of Bahia, in the northeast of the country, while Ogum in the southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul is more likely to be associated with Saint George.

Saint Sebastian is also regarded as the Patron Saint of soldiers generally, of infantrymen particularly, of athletes generally, of archers particularly and of municipal police officers.

Saint Sebastian is officially the Patron saint of the city of Chepen, La Libertad, in the north of Peru. On January 20 is the major festivities and celebrations of the city.

Historically, gay men and organizations have considered St. Sebastian to be their patron (in part due to the phallic imagery of the multiple arrows). The churches who recognize his canonization, however, do not support such claims.

Saint Sebastian in popular culture

Versions of the iconic image of Sebastian impaled with arrows appear in:

- R.E.M.'s "Losing My Religion" music video, which combines the image of the saint with other religious imagery

- Claude Debussy's "Le Martyre De Saint Sébastien", a musical piece inspired by the saint

- Philip Glass includes a short musical piece titled "Saint Sebastian" in his score for the film Mishima, a reference to Mishima Yukio's Confessions of a Mask in which a painting of St. Sebastian by Guido Reni plays a preponderant role in the main character's discovery of his own sexuality.

- On the Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds album Murder Ballads, the song "O'Malley's Bar" includes a brief reference to Saint Sebastian.

- In the 1976 film Carrie, a small statue of Saint Sebastian is present in Carrie White's prayer closet. (It is sometimes mistaken by viewers for a beardless Jesus Christ.) Carrie's mother Margaret later dies in a pose similar to the statue's.

- The chorus of the Patti Smith song "Boy Cried Wolf" references the means of Sebastian's death.

- In the TV series Lost, the hospital in which Jack Shephard and his father, Christian, work is named after the saint.

- In the film V for Vendetta, V has a painting of St. Sebastian in his home, the Shadow Gallery.

- In the film Blown Away, the statue of St. Sebastian symbolically appears throughout the film.

- In the film Suddenly, Last Summer (film), a large painting of St.Sebastial appears on a wall of Sebastian's garden.

- In Season 3 of The Simpsons in the episode "Bart's Friend Falls in Love", after Milhouse and Samantha Stanky are discovered kissing by her over-protective father, Samantha gets transferred from Springfield Elementary School to Saint Sebastian's School for Wicked Girls.

- In Season 16 of The Simpsons in the episode "The Father, The Son and The Holy Guest Star" the saint is mentioned in a comic book "Lives of the Saints" clandestinely read by Bart in a catechism class.

- In the video for the song "Zombie" by The Cranberries, the singer, Dolores O'Riordan, is depicted strapped to a tree, surrounded by children, in a style clearly reminiscent of Sebastian.

- In the Canadian film Lilies, a rehearsal for a church's re-enactment of the scene plays a prominent role in the storyline and iconography.

- A Glasgow-based band is named San Sebastian, and their CD cover and logo pictures Sebastian.[1].

- Followers of Saint Sebastian figure prominently in Loren D. Estleman's "Amos Walker" novel, "Nicotine Kiss". In the private eye novel, they meet at "The Church of the Freshwater Sea".

- The power metal band, Sonata Arctica made a song called San Sebastian. (Equivalent in Spanish) but it refers to the basque city san sebastian or donostia in basque

- The novel "Hotel Transylvania", by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, features a villain named Saint Sebastien.

- The rock band Instar wrote a song titled "Saint Sebastian" describing a child's reacting to a painting of the saint.

- In the Val Lewton RKO film I Walked with a Zombie a figurehead of St. Sebastian is featured in the garden of the Hollands' residence, and is the name of the fictional island that the movie takes place on. The same island also features in Lewton's The Ghost Ship, and the RKO Carney and Brown film Zombies on Broadway

- In her short story "Everything That Rises Must Converge" Flannery O'Connor tells us that the character Julian "appeared pinned to the door frame, waiting like Saint Sebastian for the arrows to begin piercing him."

- St. Sebastian's Hospital is featured in three episodes of the series House. First season 2 episode 9, "Deception", and again in season 3 episode 10, "Merry Little Christmas".

- Several films have been made about the life of Sebastian, mostly focusing on his iconic execution. Most notable of these are Derek Jarman's Sebastiane (scripted entirely in Latin, and with considerable nudity) and Bavo Defurne's 1996 short film, Saint [2].

- Oscar Wilde, in his last years after being released in 1897 from his prison term on charges of homosexuality, lived in a self-imposed Parisian exile under the assumed name of "Sebastian Melmoth" - the first name derived, in Wilde's own words, from "The famously penetrated Saint Sebastian".

- The television show Millennium has an episode entitled "The Hand of St. Sebastian" (2nd season).

See also

Discussion of the image of St. Sebastian in the paintings of Mantegna

Notes

- ^ Commemorated in his feast day

- ^ Reliquary of St Sebastian. Metalwork. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved on 2007-08-17.

- ^ Acta S. Sebastiani Martyris, in J.-P. Migne, Patrologiae Cursus Completus Accurante (Paris 1845), XVII, 1021-1058; the details given here follow the abbreviated account in Jacob de Voragine, Legenda Aurea.

- ^ Ebenezer Cobham Brewer, A Dictionary of Miracles: Imitative, Realistic, and Dogmatic (Chatto and Windus, 1901), 11.

- ^ Legenda Aurea.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia 1908.

- ^ (For a discussion of the image of St. Sebastian in the paintings of Ribera, see: Williamson, Mark A. "The Martyrdom Paintings of Jusepe de Ribera: Catharsis and Transformation", PhD Dissertation, Binghamton University, Binghamton, New York 2000 (available online at myspace.com/markwilliamson13732)

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia 1908: "Saint Sebastian"

- Rev. Alban Butler, The Lives or the Fathers, Martyrs and Other Principal Saints, vol. I An elaboration of the Acta, introducing many circumstial details.

- Patron Saints Index: Sebastian

- Legenda Aurea: Life of Saint Sebastian

- Iconography of Saint Sebastian

- David Woods, "The Military Martyrs"

- Sebastian the Martyr, Greek Orthodox Church

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire